Art and Experimentation: John Dewey's Modernist Legacy

Josef Albers, “Six Variants” (1969)

Although John Dewey remains a cornerstone of American educational thought, his books are not usually associated with artistry—except in the sense that reading them can feel like watching paint dry. Oliver Wendell Holmes once described Dewey’s work as “incredibly ill written”…which is generous. Even when Dewey addresses aesthetics directly—for example, in Art as Experience (1934)—his dogged commitment to naturalism (the material world) and functionalism (judging value in terms of outcomes) tends to overshadow deeper commitments to beauty and creativity.

And I say this as someone who likes Dewey!

A related problem is that visual representations of Dewey’s educational methods almost always depict his time at the University of Chicago Laboratory School: either black-and-white photographs of children hammering wood or carding wool, or the black-and-white sketches that appeared in The School and Society (1899). Not only do these images seem dated, they convey a far too literal a sense of Dewey’s approach.

Children modeling rabbits out of clay at the University of Chicago Laboratory School

Child’s sketch from “The School and Society.”

A less predictable, more abstract but no less applied alternative appears in Eva Diáz’s wonderful new book about art and experimentation at Black Mountain College. (Diaz joins earlier explorations of Black Mountain and seems to be part of a resurgence of interest in the school). Dewey was on Black Mountain’s advisory board and his work deeply influenced Josef and Anni Albers, the German emigrés and Bauhaus designers who became some of its first professors. It is through the teaching of Josef Albers, specifically, that we find interesting visual representations of Dewey’s thought.

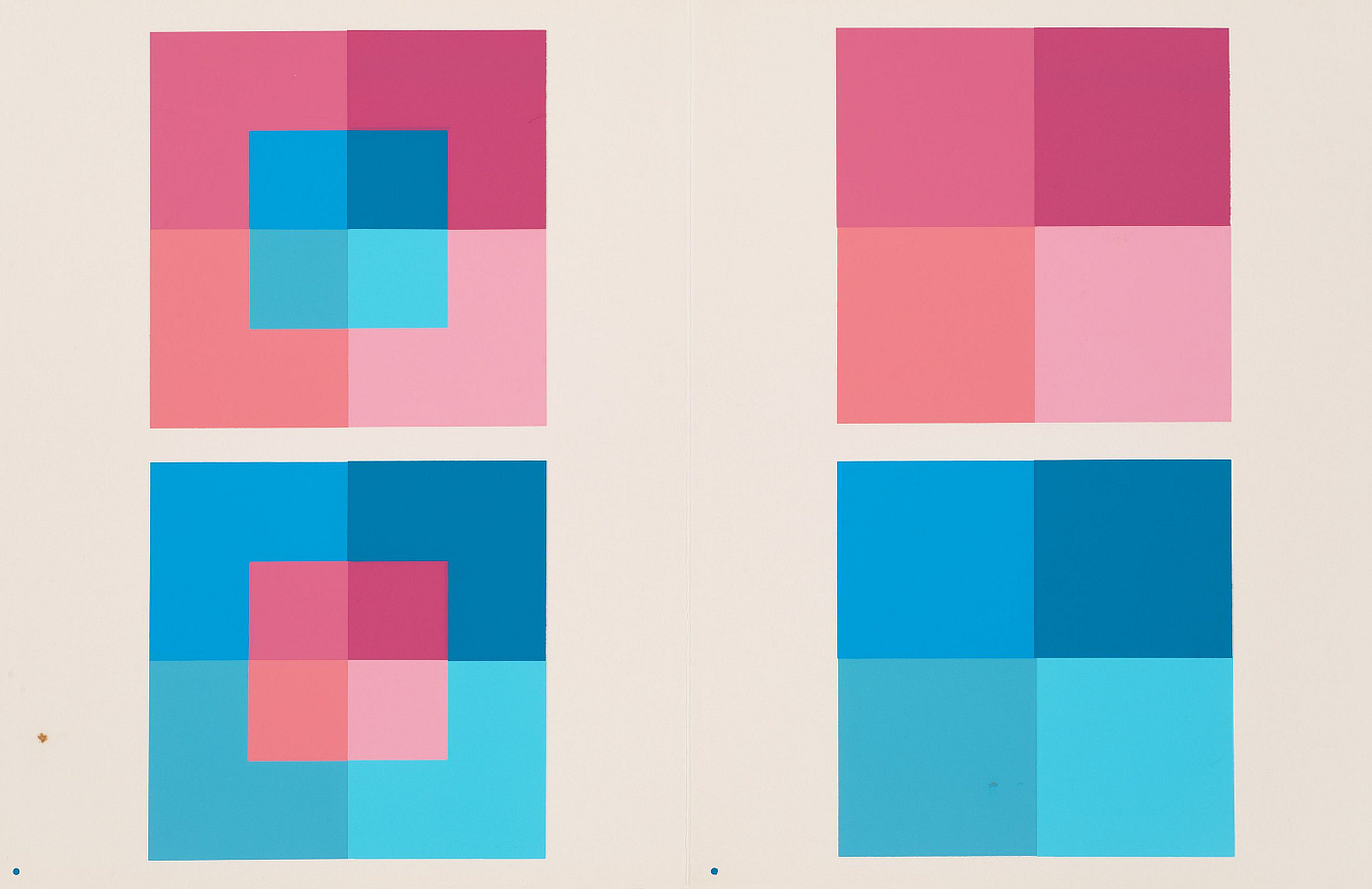

Of his own educational goals, Albers said, “I want to open eyes.” His students learned to see the world anew by overcoming subconscious habits. Drawing classes “were conceived as a ‘test of seeing,’” in which (through “an ordered and disciplined testing of the various qualities and appearances of readily available materials such as construction paper and household paint samples”) students discovered the applied interactions of various shapes and colors. In one activity, Albers had them write their names backwards, in cursive, with their non-dominant hands. In another, he had them overlay squares of paper in different colors. “The ability to see color and color relationships,” Albers insisted, “is more important than ‘to know about’ color.” As Diáz notes, “He stressed the experience, rather than any definite outcomes, of a laboratory educational environment, and promoted forms of experimentation and learning in action that could dynamically change routine habits of seeing.”

Josef Albers, “Interaction of Color” (1963)

Albers also stressed the tactility and subtle symmetries between different materials. Like scientists, his students tested elements of “compression, elasticity, and firmness…through folding and bending,” arriving at new insights about “the internal organization of forms and their relation to one another” and forming an appreciation for “dynamic relations” rather than “strictly symmetrical or mathematically predictable ones.” In all of this, Albers echoed Dewey’s principle that truth was inductive and evolving, not a product of pure reason or received practice but the outcome of sustained attention and concrete experience.

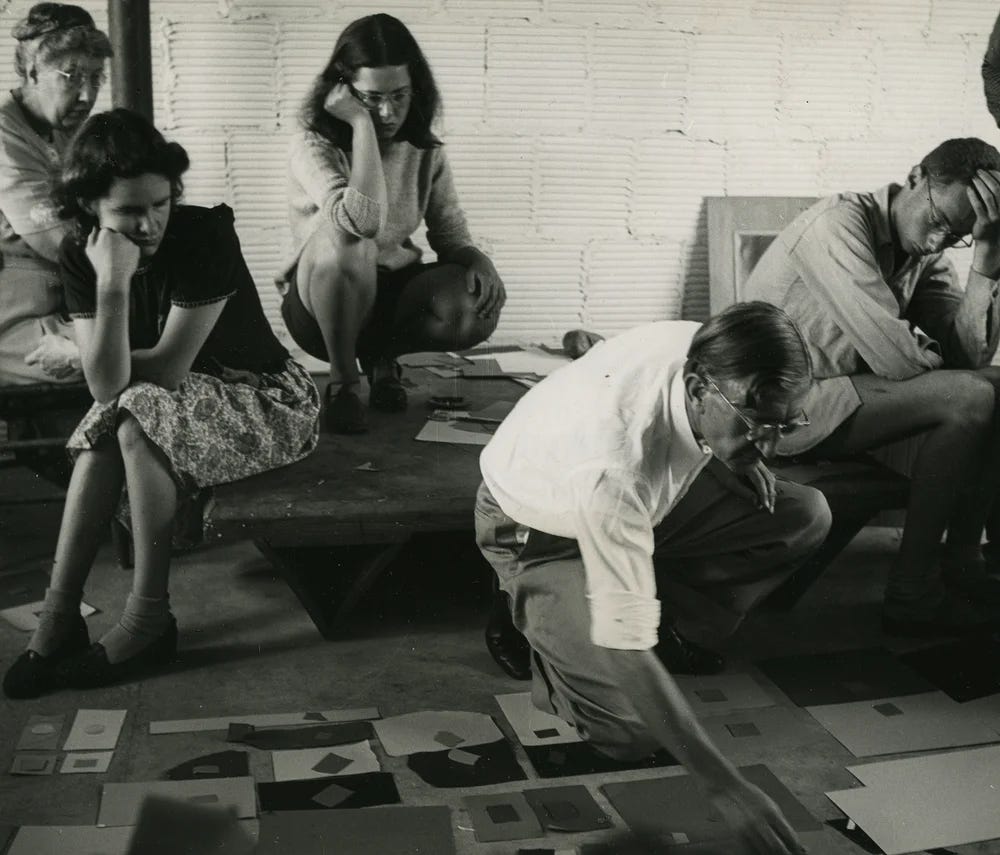

Josef Albers teaching lessons (c. 1940s)

Of course, “experience” is a capacious term for Dewey, particularly when applied to art. All sense impressions constitute a form of experience, as does systematic experimentation and induction into the accumulated wisdom of history and tradition. But aesthetics is the highest form of experience, “experience in its integrity.” It is a fullness of being that resists “submission to convention” and ties skill, emotion, and thought together into “a single whole.” Like Alfred North Whitehead, Dewey sees aesthetic experience as a temporal process, in which the individual participates in an unfolding of harmony and rhythm. At the same time, aesthetic experience can appear in almost any undertaking, not just painting or sculpting but eating, reading, or washing dishes. To be fully artistic, these activities must incorporate elements of both activity and passive contemplation. As Dewey writes, “art, in its form, unites the very same relation of doing and undergoing, outgoing and incoming energy, that makes an experience to be an experience.” Philosophers of education have recently equated this form of perception with wonder and receptivity. One could say, with Arthur Kestenbaum, that the aesthetic is as close as Dewey gets to a state of enchantment.

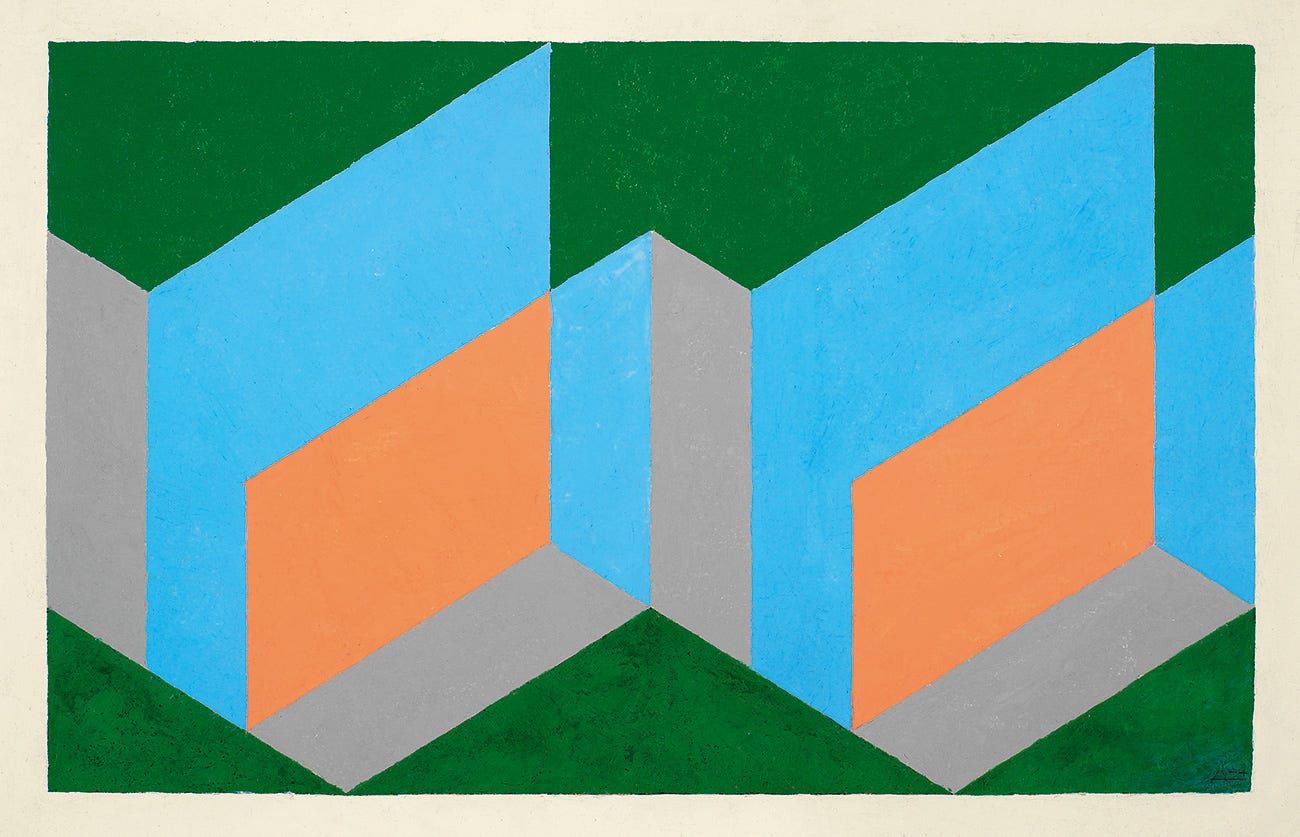

Joseph Albers, “Portfolio 1, Folder 33, Image 1 Framed Silkscreen” (1972)

Albers was also explicit about the ethical implications of his teaching. While one might not immediately see connections between green paint swatches and questions of right and wrong, Albers pointed out that “without comparison and choice there is no value.” He stressed the need for inquiry through art. One should not merely copy the old masters, but pursue personal expression and judgment by testing the qualities and limitations of physical substances. He warned that we should not be “afraid that thinking and planning—necessary in all human activities—will spoil the painting of a picture.”

Finally, like Dewey, Albers recognized that modern art and progressive educational techniques both advanced the possibilities of social reconstruction. “I believe dominating education methods in this country are not at all typically American,” he wrote, “with their stereotyped requirements, standardized curricula, and mechanized evaluation of achievements. Why do we still have the belief in academic standards while our living reveals variety, youth, and freshness…?” A truly democratic society was one that liberated individuals to fulfill their potential through collective enterprise and shared decisionmaking, and that was no less true in the classroom than in the government.

Josef Albers, “Tautonym B” (1944)

Diáz’s book includes second and third sections, focused on John Cage’s musical performances and Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes. Cage and Fuller were two other visionaries who took up residence at Black Mountain—both interesting in their way, I suppose, but more in line with the obnoxious, off-beat self-promoters that experimental colleges always seem to attract. In Albers, we find another type of experimental educator, the kind who combines aesthetic play with ascetic sincerity, and who helps us reconsider the sources of beauty in our daily lives.