Arts and Sciences

Chesley Bonestell, “Saturn as Seen From Titan” (1949)

Scientific breakthroughs open new vistas. They reorient our perspective on the world and, in the process, inspire wonder and delight. Science depends on intuition, imagination, and elegance, and thus it is inescapably aesthetic. Indeed, the connections between these qualities have fascinated scholars from Plato to the present. (As Richard Holmes notes, it is hard to beat the early nineteenth century on this front: Dinosaurs! Balloons! Comets! Deep-sea diving! What a time to be alive!)

John Martin, “The Country of the Iguanodon” (1837)

E. W. Cocks, “Balloon Leaving Dover” (1840)

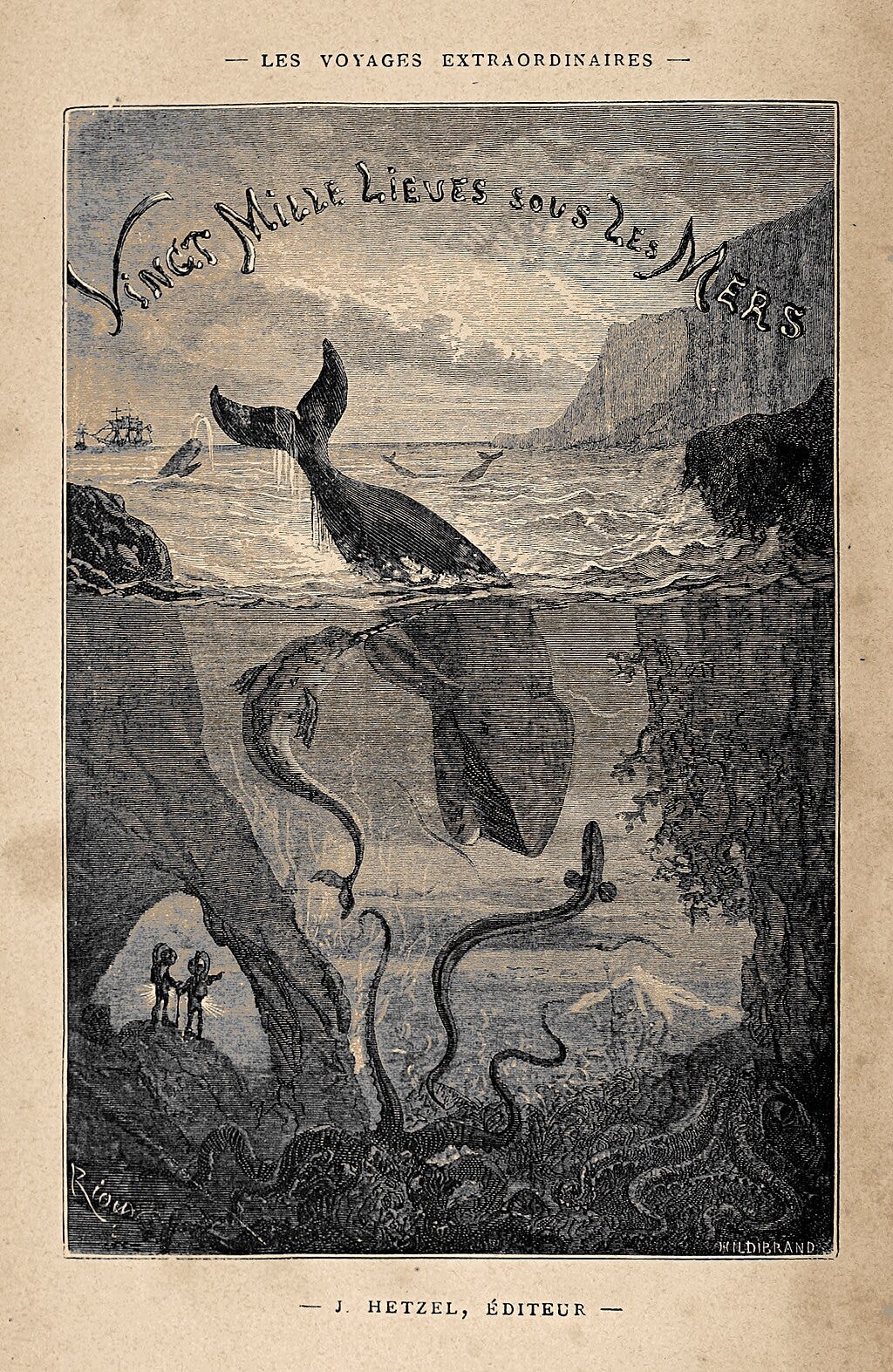

Edouard Riou, “Vingt Mille Lieues Sous Les Mers” (1871)

Although there are many defenses of arts education in school (e.g., see Laura d’Olimpio’s excellent new book), it seems like we should acknowledge the power of aesthetics in other areas of the curriculum as well, and especially in science classes. For not only does science inspire new forms of art, art often informs our inquiries into nature. Jules Verne, Isaac Asimov, and other science fiction writers remain touchstones for the interpretation and application of developments in fields from astronomy to AI, and have been cited as inspiration by generations of working scientists. When it comes to understanding the world around us, there are no firm lines between style, imagination, and empirical facts.

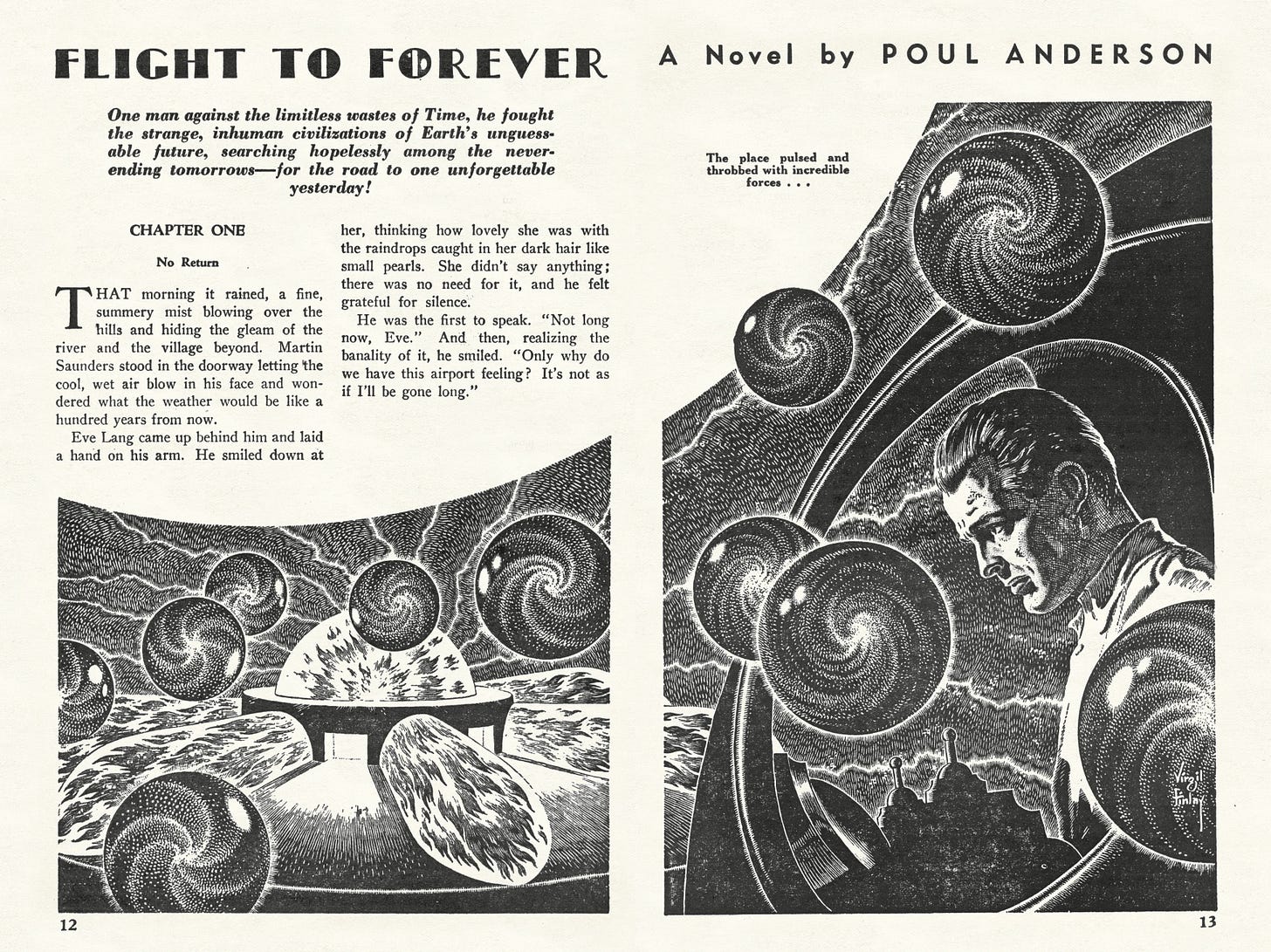

Virgil Finlay, “Flight to Forever” (1950)

Blurring the line between art and science can be a problem, of course, when it leads to conceptual confusion or outright errors. For instance, the Bohr model of atomic structure (which envisions the atom as a miniature solar system, with the nucleus orbited by solid little electrons) remains widespread in high school classrooms and textbooks because it is easily grasped, although it fails to capture the weird, indeterminate characteristics of wave functions and quantum mechanics. For decades, popular science books depicted dinosaur species from entirely different geological eras locked in battle, and while many books have since caught up with discoveries of feathered therapods, they have yet to incorporate extensive research on dinosaur behavior or to abandon Jurassic Park-style attacks for more prosaic biological realities.

The worst (most sensationalistic) example from my childhood is probably Roy Gallant’s Our Universe (1980), a popular astronomical encyclopedia. A friend owned a copy, and I eagerly read it every time I went to his house. Suffice to say, it confused me. The book had explanations of star formation and the moon’s orbit right next to silly sci-fi drawings of aliens ice-skating on Europa or belching liquified iron on Venus. Were these drawing supposed to be taken as seriously as the book’s scientific information? What did they suggest about its overall credibility? Even as a child, I suspected that these were not really examples of scientific imagination but of crass marketing.

Don’t get me started on all the Loch Ness Monster and Bigfoot books that were (and remain) staples of elementary-school libraries and book fairs…

Roy Gallant, Our Universe (1980)

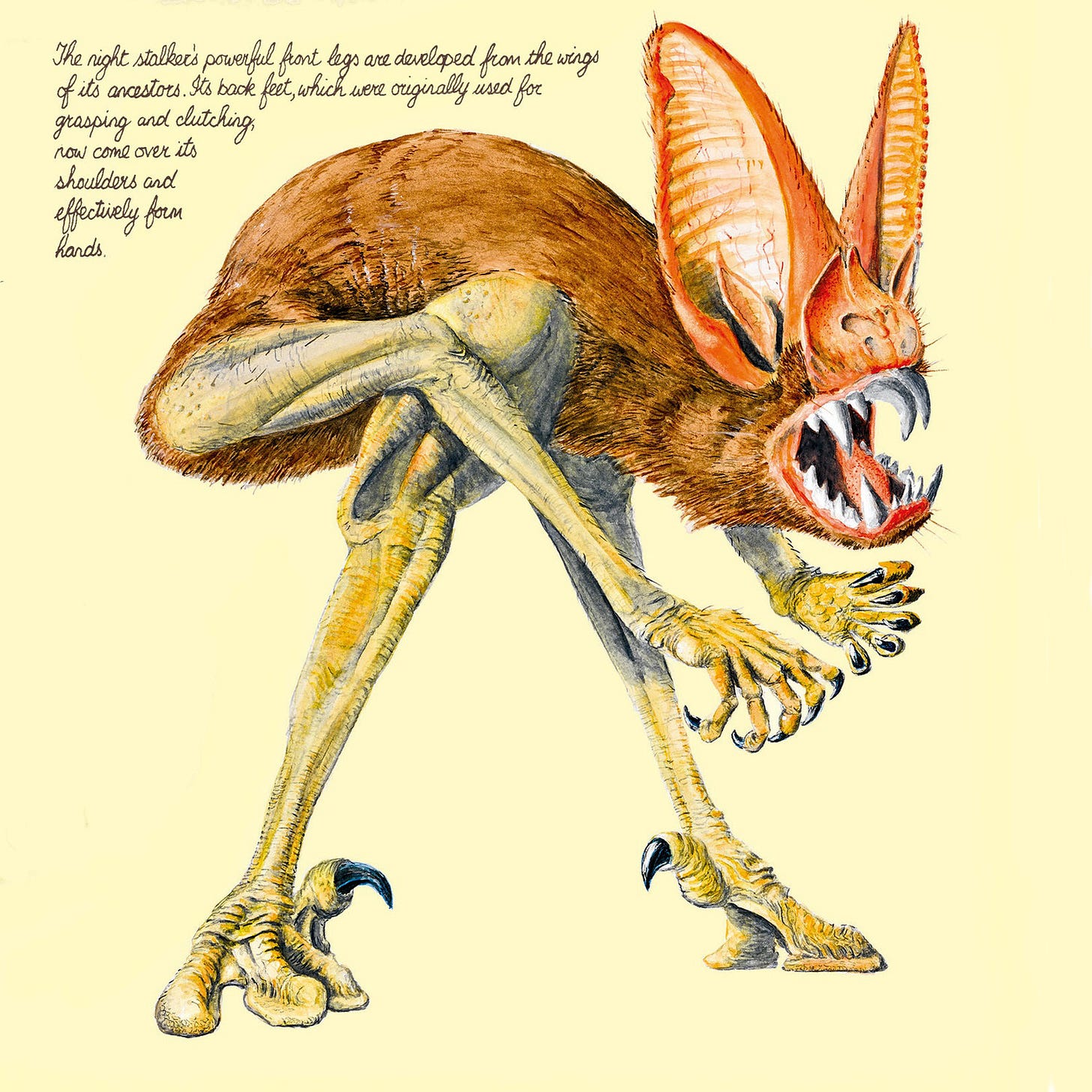

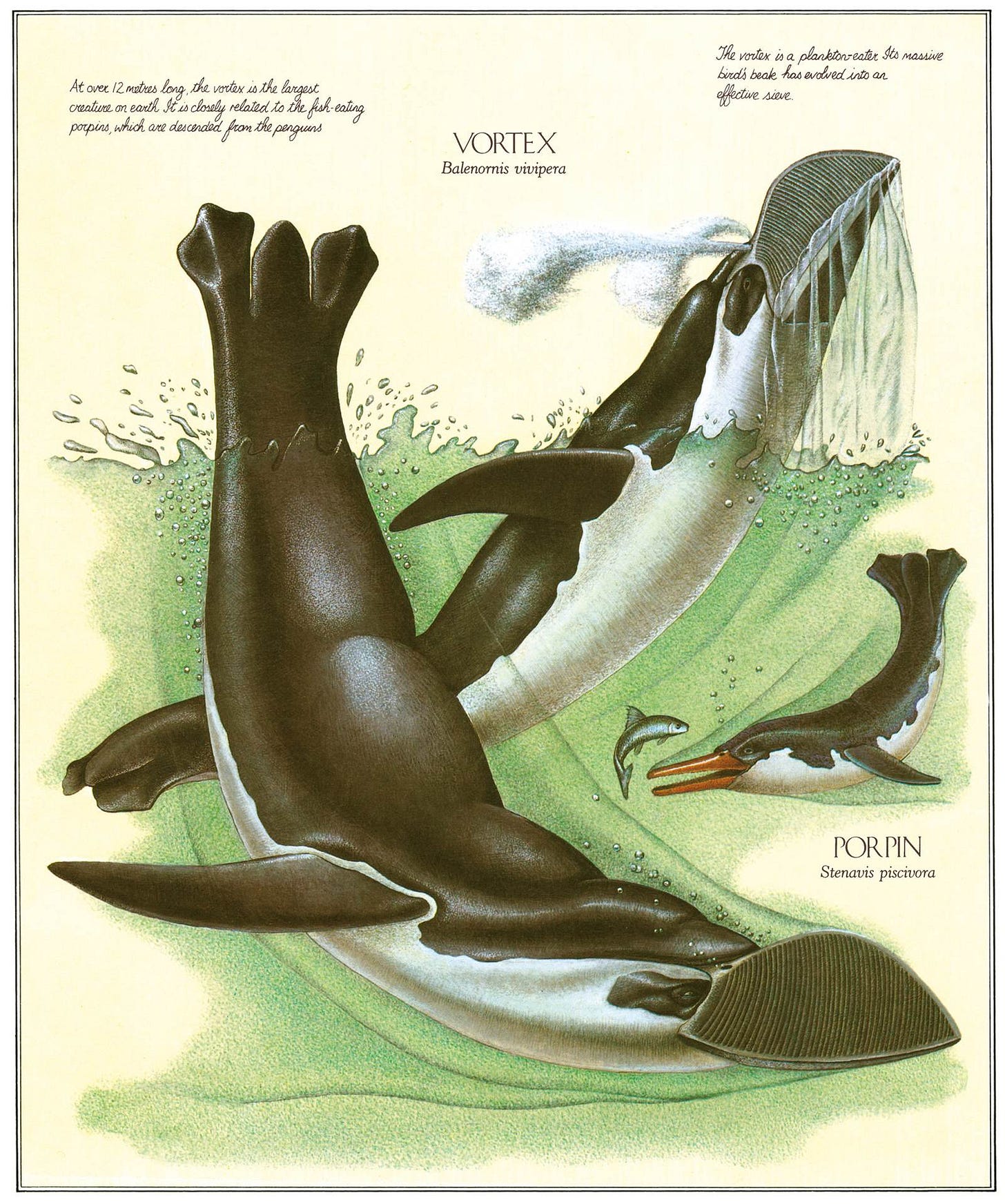

A better use of scientific aesthetics, which appeared at about the same time (and which I loved in middle school) is Dougal Dixon’s “After Man,” which could be fairly described as speculative biology. Dougal frames his book as a field guide written a million years after the extinction of humanity. Like Gallant, he fills it with sensationalistic illustrations (not least, giant flesh-eating bats that gave me nightmares), but he aligns these closely with real biological principles, including trophic niches, convergent evolution, island colonization, and gigantism. Indeed, the book encourages readers to reflect on how the far-out species in its pages are not so different from the wondrous oddities that already surround us today, and to consider how the latter got that way.

Dougal Dixon, “After Man” (1981)

Dougal Dixon, “After Man” (1981)

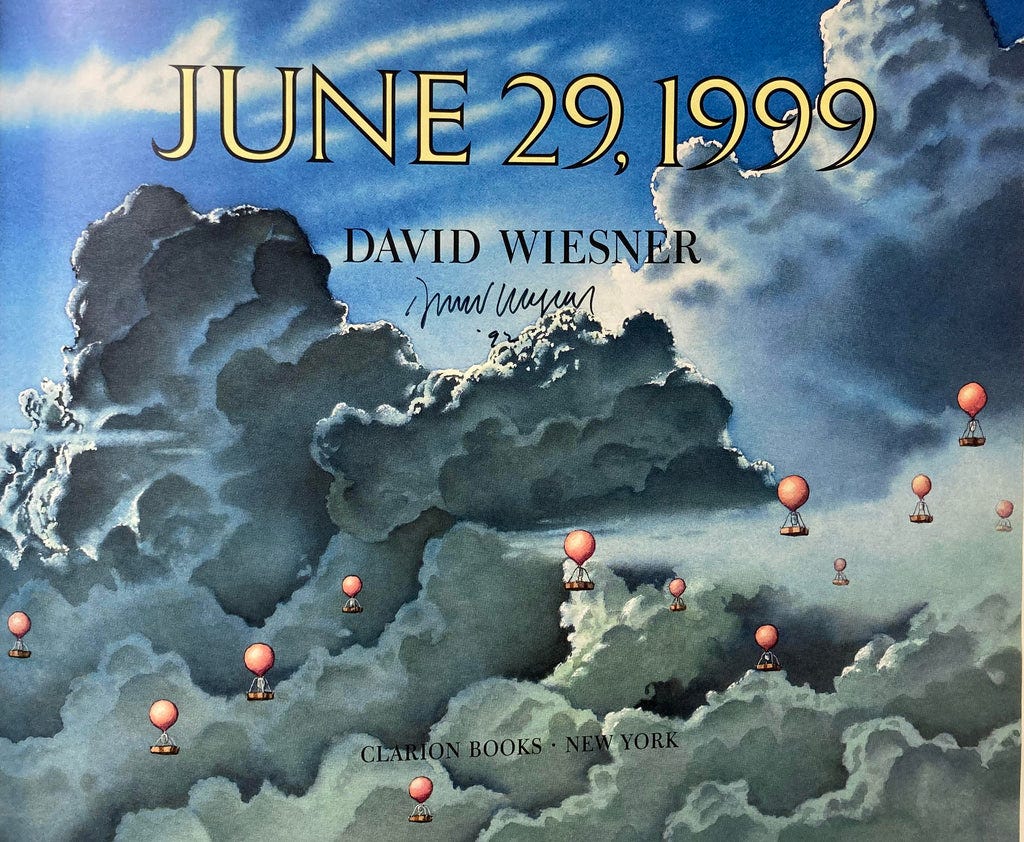

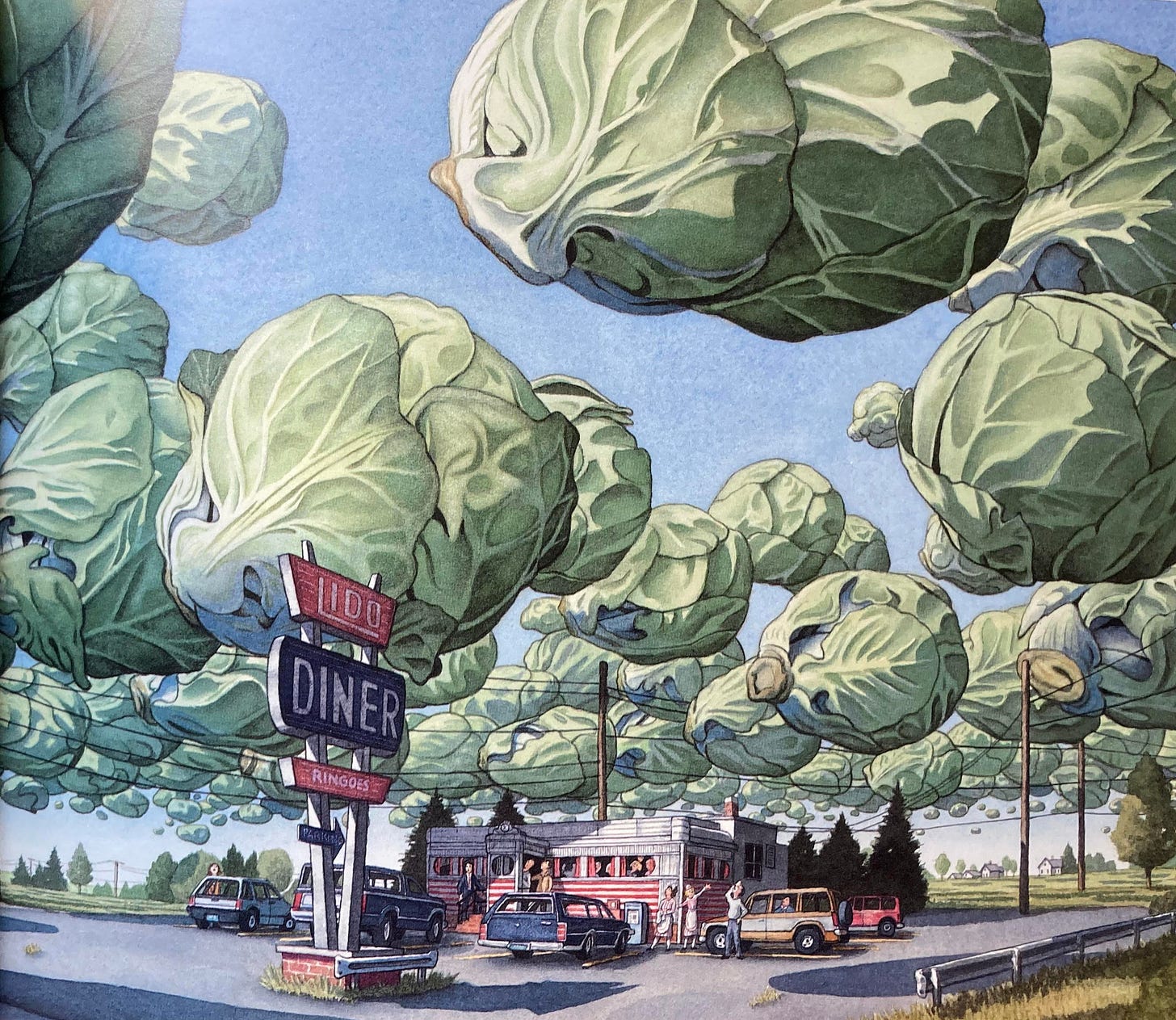

Art that straddles the boundaries between science and fiction seems to do best when it plays the first part straight. Another great example is David Wiesner’s picture book, June 29, 1999 (1992), which features an earnest middle-schooler who is curious about the effects of solar radiation on plant growth. On her own initiative, she obtains weather balloons, explains her hypothesis to distracted classmates and an amused teacher, and releases dozens of seedlings into the upper atmosphere. The background details are all correct, and (interestingly) my former colleague has done similar research with the International Space Station.

Like all good science fiction, however, something goes very wrong…

No child will mistake Wiesner’s book for scientific truth, but it does raise interesting possibilities about biological and meteorological research and encourages children to explore their own questions seriously…with the possibility of the unexpected always looming above them. And isn’t that the possibility that fuels all education? As the philosopher Philip H. Phenix once wrote, “Wonder is the hovering shadow of an answer resident in every question seriously asked."