Dancing About Architecture

Steve Martin once said that writing about music is like dancing about architecture, so today’s post is kind of a dance—with a few thoughts about how the physical structures in which children learn become part of the learning process itself.

Scranton (PA) High School (2001)

One advantage of school architecture is its endurance, which offers opportunities for comparison and philosophical reflection across eras of schooling.

For instance, one-room schoolhouses continue to dot the American landscape, now converted into homes, shops, and museums. As I have written elsewhere, these buildings are not quaint mementos of times-gone-by but potentially radical indictments of what has replaced them. Their classrooms afforded opportunities for self-paced and cooperative learning, and (as Johann Neem has argued) required active support from their communities, calling forth judgment, deliberation, and an attachment to public space in the process. Schoolhouses were the foundation of American democracy (quite literally).

In 1909, Delaware County, Ohio, where I used to live, had up to ten schools in each township.

Most of these shared a common design, with three high windows along the sides and a peaked roof, though some had interesting embellishments, such as separate side-entrances for boys and girls. And while some were slightly dilapidated wooden structures, most were built of brick, communicating permanence and local respectability.

High schools from the 19th and early 20th centuries convey similar messages. Often describes as “cathedrals of learning,” these tended to have imposing edifices and cupolas. The underlying moral messages weren’t particularly subtle. In Delaware, for instance, one finds two plaques on the former Frank Willis High School, reading: “Education Adorns Riches and Softens Poverty” and “New Occasions Teach New Duties.” In Madison, Wisconsin, East High School was built in the “collegiate Gothic” style, with turrets and gargoyles, not because most of the students would ever attend college, but to impress on them the dignity of their studies.

Frank B. Willis High School (Delaware, OH)

East High School (Madison, WI)

By the 1950s, with suburbanization and the spatial requirements of “comprehensive” programing (gyms, workshops, etc.), most of these high schools were abandoned for the expansive and inexpensive cinderblock construction that persists today. The shift has left melancholy ruins in cities like Detroit, and has fueled critiques from a certain type of online conservative. President Trump recently signed an executive order encouraging classical architecture for federal buildings, but public schools are funded by municipal and county governments, not the federal government.

Detroit, Cooley High School (1928)

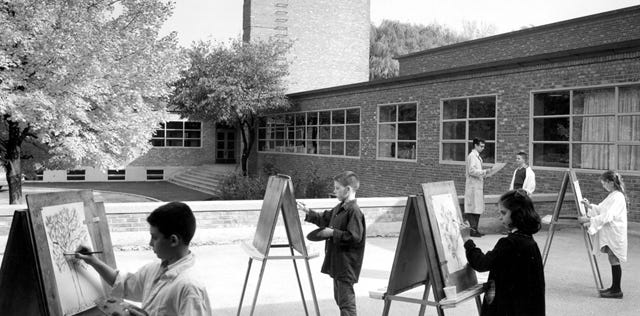

I am less interested in lamenting a lost past than in encouraging local experimentation in the future. There have been ongoing experiments in school design, carried out by forward-thinking boards and inventinve firms, that enable new types of teaching and learning—whether in communion with the landscape, in collaboration with classmates, or simply in confrontation with inspirational combinations of line and color.

Crow Island Elementary School (Winnetka, IL)

It will be interesting to see what we value in schools moving forward, and how those values will appear in physical form.