Irony as Invitation

“The Skunk” (2015)

Ten years ago, Patrick McDonnell and Mac Barnett published a charming children’s book called The Skunk, in which a man in a black-and-white tuxedo, a cummerbund, and a red bow-tie discovers a skunk on his doorstep. He carefully steps around it and walks downtown. Looking over his shoulder, he finds that the skunk is walking in the same direction. He soon comes to an unsettling realization…

Uh-oh.

The subsequent chase takes twists and turns, all the funnier because of the unexplained and ambiguous menace of the skunk. Who is he? What does he want? By the time the protagonist takes to the sewers, adult readers will have come to their own realization: they are reading an absurd pastiche of Graham Greene’s The Third Man (1949).

Joseph Cotten in “The Third Man” (1949)

The oblique reference to film noir captures something at the heart of all good children’s books and perhaps at the heart of all good education: irony as an invitation into adult culture.

The best summary of this phenomenon is an exchange I saw a few years ago on Twitter (back when that platform tended toward the whimsical and profound), which begins with a reference to Peter Lorre, another noir icon.

Peter Lorre in “M” (1931)

The original post pointed out the seemingly ridiculuous premise of Looney Tunes:

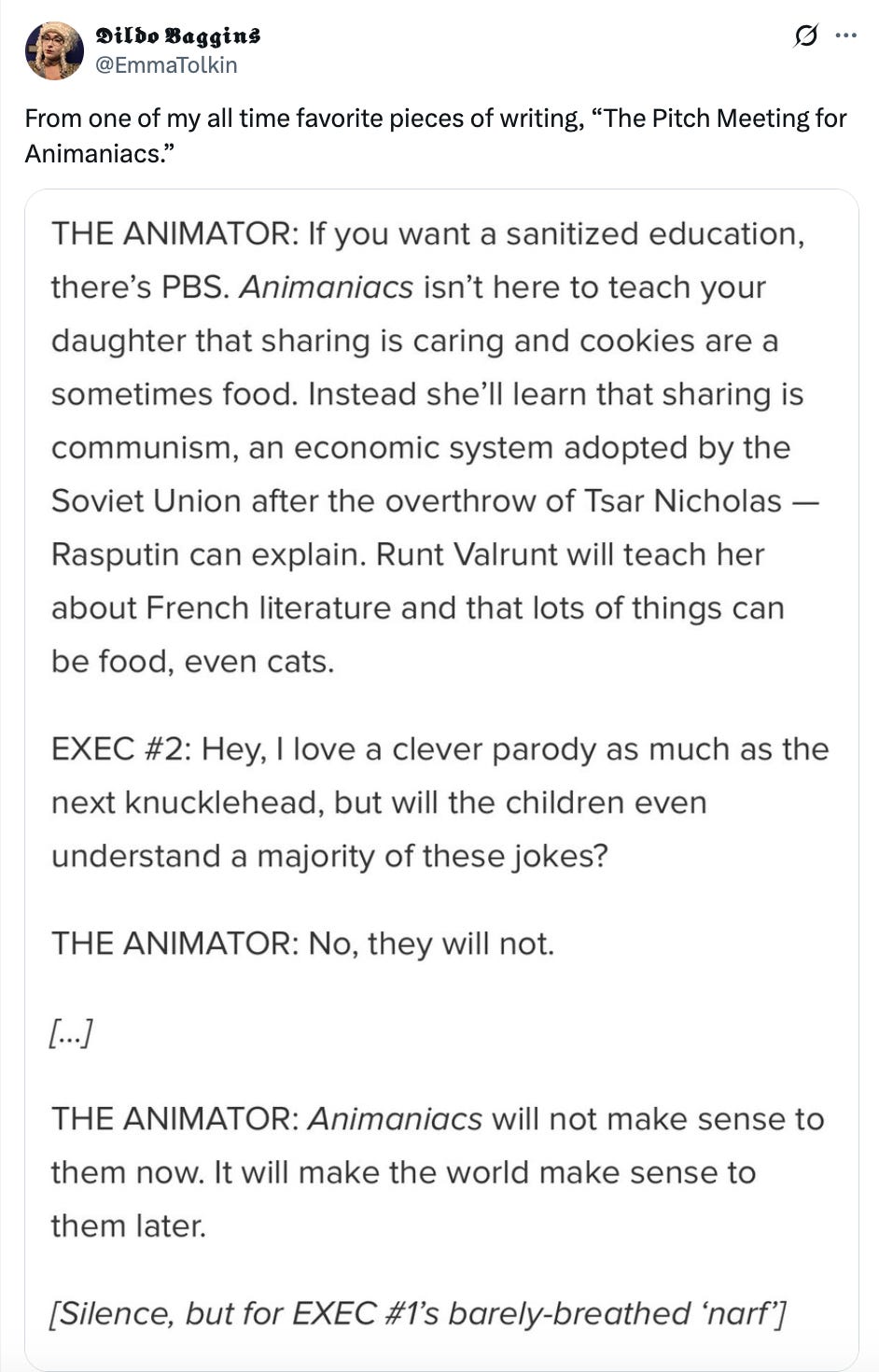

The cultural references in Looney Tunes were never age appropriate or even remotely comprehensible to young viewers. Why didn’t that seem to matter? Another poster responded with a facetious essay about the revival and apotheosis of the form: the screwball 1990s cartoon, Animaniacs.

Laying the foundation for later meaning—as Whitman puts it, “Building, equipping like a fleet of ships, immortal ships,/ Soon to sail out over the measureless seas,/ On the soul's voyage”—is essentially an exercise in irony. It depends on movements and knowledge that the adult is aware of and the child is not, but that nevertheless impart a form of knowingness or worldiness to the latter.

The problem is that many philosophers, most famously Jean-Jacques Rousseau, have denounced this sort of education, which they worry will breed duplicity and insincerity in children. Indeed, Rousseau argues that anything but literal, experiential lessons will wrench the student out of childhood altogether, corrupting them with abstraction and conventionality.

Humor certainly carries this risk. As the philosopher Matt Dinan writes, “Jokes, at their best, are invitations to shared understanding of the goodness of human life; at their worst, they’re an exercise in cruelty or debasement.” However, Dinan sees a promising educational path in the telling of “dad jokes.” As Dinan sees it:

Dads use these jokes to put themselves out there so that the little person listening to the joke can become knowingly complicit, and maybe learn something about how to be funny. But they are perplexing because they expose the teller in a way directly opposite to the regular functioning of a joke. If wit allows us a certain autonomy, dad jokes make us vulnerable. A dad joke is an un-joke because your goal is not your own freedom, but someone else’s.

Here, knowingness is not a means of detachment or superiority but the opposite: an invitation into a loved and cherished body of knowledge. Like most aspects of culture, puns and catchphrases are essentially arbitrary and cannot emerge from natural necessity or constructive experience: they must appear to the child at first as black-and-white facts—just the kinds of things that one’s dad says—and they can only take on meaning in the context of paternal love.

Though he does not reference it directly, Dinan’s argument draws heavily from Søren Kierkegaard’s Philosophical Fragments (1844), which expounds on the role of irony in Socratic thought and on the role of paternal (indeed, Godly) love in imparting subjective standards of reason. For our purposes, it is enough to point out that imparting knowledge in the context of deep interpersonal or intersubjective connections—being invited into a shared experience—seems to answer Rousseau’s concerns about moral corruption. In the process, it also elicits from the student a genuine desire to know things.

Educators of a certain age will probably remember the “cultural literacy” movement that lasted from the 1980s to the early 2000s. While I completely support rich cultural literacy, which strikes me as the entire point of education, it cannot happen (as it actually did) through the deadening literalness of “direct instruction” or lists of content standards. Nor can cultural literacy be reduced to instrumental goals of economic mobility or civic cohesion. Culture must be an end in itself, as is the creation of cultured individuals.

The most effective way of communicating cultural ideals, in children’s books and generally, seems to be the incorporation of touchstones: rich aesthetic images, repeated and deepened as students mature, that can bring children from black and white to shades of gray. If some aspects of adult culture seem a little silly to children, others become strangely appealing. It is through this sort of loving inducement that we can best share beauty and truth with our students.