Meg White Comes Through

You may remember, a couple years ago, when some random reporter decided to go on Twitter and say the dumbest thing in the history of rock n’ roll.

Umbrage was taken (mostly around perceived sexism), defensive rejoinders were posted. Meg White, of course, remained silent.

What was interesting about the whole thing was that so many of White’s fans seemed to offer only faint praise and backhanded compliments in her defense. (She was “the right drummer for that band,” etc.) Few of them explained why White is so great or how she became the heartbeat of a generation.

To my ears, White’s greatness comes from the raw self-expression that drives all rock n’ roll, but for her that expression is rooted in responsiveness. White exudes presence (and escapes the self-consciousness that seems to haunt her away from the drum kit) because she thrives in a paired relationship. The simplicity of the band’s style (in comparison to improvisational jazz, say) just makes the dynamic clearer.

Theorists have identified a similar relational quality underlying other forms (maybe all forms) of artistic expression. For example, Walter Benjamin contrasts modern, stereotyped reproduction with the “authenticity,” “uniqueness,” and “aura” of a live performance, without which both the performer and the audience are corrupted and debased. He offers the shift from theater to film as an example:

The film actor lacks the opportunity of the stage actor to adjust to the audience during his performance, since he does not present his performance to the audience in person. This permits the audience to take the position of a critic, without experiencing any personal contact with the actor….“The film actor,” wrote Pirandello, “feels as if in exile—exiled not only from the stage but also from himself. With a vague sense of discomfort he feels inexplicable emptiness: his body loses its corporeality, it evaporates, it is deprived of reality, life, voice, and the noises caused by his moving about, in order to be changed into a mute image, flickering an instant on the screen, then vanishing into silence . . . The projector will play with his shadow before the public, and he himself must be content to play before the camera.”* This situation might also be characterized as follows: for the first time—and this is the effect of the film—man has to operate with his whole living person, yet forgoing its aura. For aura is tied to his presence; there can be no replica of it. The aura which, on the stage, emanates from Macbeth, cannot be separated for the spectators from that of the actor.

Martin Heidegger likewise writes about truth being “uncovered” through inter-subjective relationships with the world. In art, he writes, our consciousness is called toward creativity through a recognition of “otherness,” an almost Taoist stance of receptivity, disclosure, and reciprocity with creation. When contemplating an artwork, we must first

grant to the thing, so to speak, a free field in which to display its thingness quite directly. Everything that…might interpose itself between us and the thing must, first of all, be set aside. Only then do we allow ourselves the undistorted presence of the thing. But this allowing ourselves an immediate encounter with the thing is something we do not need either to demand or to arrange. It happens slowly.

There is an organic and unplanned quality to this kind of relationship, an interplay that unfolds differently according to place and time; that appears almost magically, through grace; and that ultimately becomes constitutive of sincerity and selfhood. (In the music world, this quality seems to have grown attenuated in recent years.)

Meg White found a sound that was inimitably her own, in a partnership that would lose its magic without her. (As many people have pointed out, Jack White’s solo career—backed by much “better” drummers—has been just okay.) And that is why—to quote Questlove, who should know—criticism of her technique is “out of line as fuck”: it is not only sexist, not only ad hominem, but seems hostile to any “human element” in music at all.

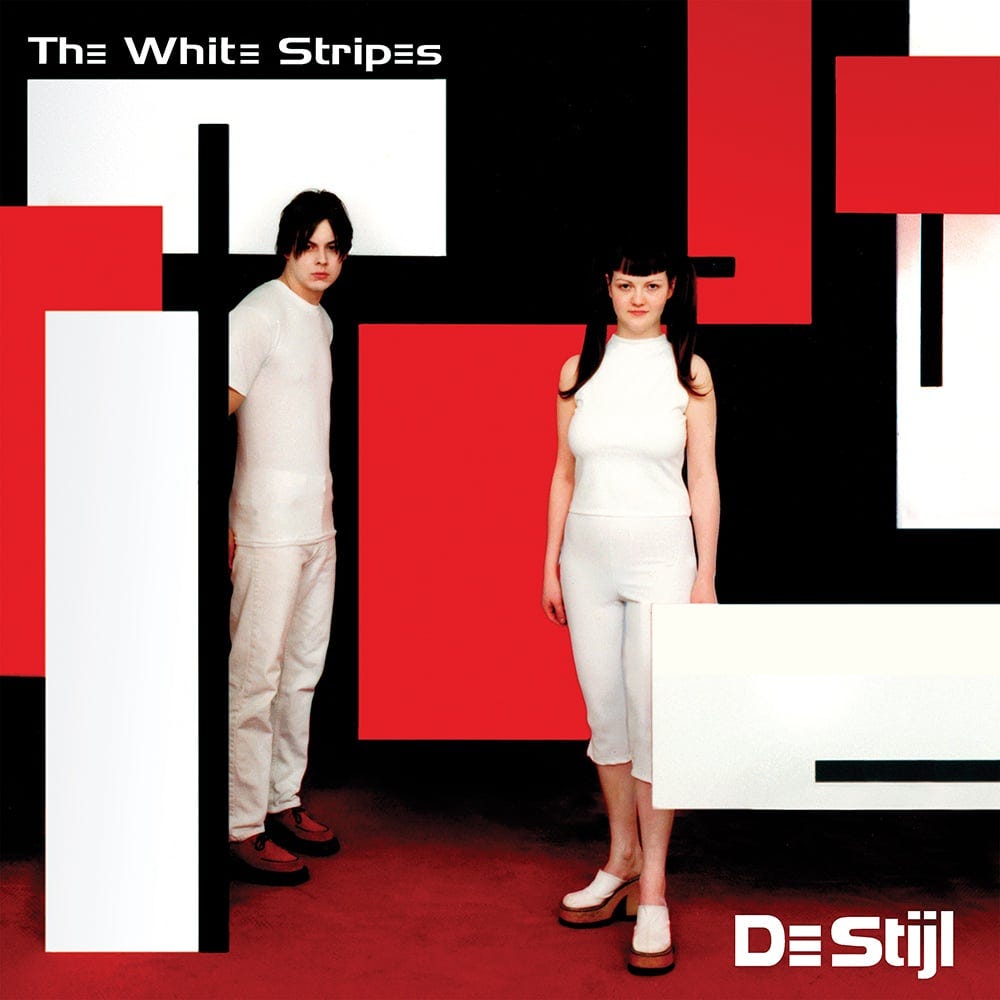

For me, the humanity behind White’s drumming puts a slightly different spin on the band’s overall aesthetic. Jack White has never been shy about the influence of artistic modernism on the White Stripes’ color pattern. (They have an album called De Stijl, for Pete’s sake, after the eponymous Dutch art magazine.)

De Stijl (2000)

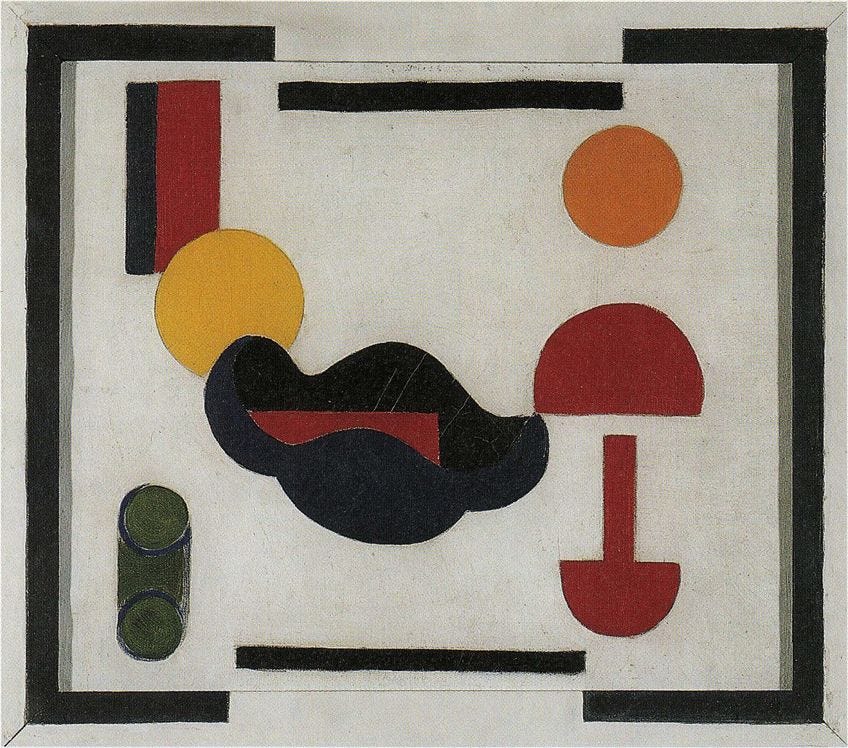

What is striking about so much of the art of the 1920s, however, is that what was supposed to be shockingly abstract and almost mechanically produced at the time now looks so charmingly homemade. Indeed, many of the era’s paintings and sculptures seem to have more in common with the arts-and-crafts movement than they do with later modern and post-modern styles.

Vilmos Huszár, “Dancing Figure no. 3” (1929)

Theo van Doesburg, “Still Life (Composition V)” (1916)

Piet Mondrian, “Composition no. 1, with Red and Black” (1929)

Jan Wils, “Red Chair” (1920s)

This kind of stripped-down simplicity focuses one’s attention on the “human element” in art. In White Stripes arrangements, it does not “cover” for White’s unskilled drumming, as critics and defenders both seem to imply, but lets her shine through as a herself, and in doing so captures something incredibly elusive, in music and in life.

The same type of simplicity and presence might have something to teach us about a child’s sense being in the classroom, where a few beats of percussion can have profound effects on self-concept and belonging, and thus on one’s enduring sense of personhood. In the words of another famous Meg, “Maybe I don't like being different, but I don't want to be like everybody else, either.”