Purity and Portraiture

A lot of my work right now deals with the concept of holiness in education, both (1) orienting children toward sources of infinite meaning—those topics that are worthy of veneration and deep study, invite individuals into religious, political, and cultural traditions, and are ultimately constitutive of human identity; but also (2) affirming that children themselves are sources of infinite meaning—to quote Friedrich Schiller, that for “a moral and sensitive person, a child will be a sacred object.”

Schiller’s line is usually cited as a Romantic celebration of infancy and innocence (a common trope in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art), but I would like to discuss a different type of holiness here: a type of adolescent purity that often appears in portraiture.

Consider Abbott Handerson Thayer’s painting, “A Virgin” (1891), which depicts Thayer’s three children: Gladys (age five), Mary (age thirteen), and Gerald (age eight).

Abbott Handerson Thayer, “A Virgin” (1891)

Over the previous decade, two of Thayer’s other children had died in infancy. His wife, Kate Bloede Thayer, was hospitalized with severe melancholy in 1888 and would also die in 1891, the year that “A Virgin” appeared. An earlier portrait already shows Mary and Gerald in a state of grief, but here we have Mary striding into the future, leading her brother and sister by the hand, an angel of protection and redemption, patterned on the ancient Greek sculpture of Victory.

The Nike of Samothrace

Preliminary Study for “A Virgin” (1891)

It is unsurprising that Thayer would turn to his family during such a difficult time. Indeed, he discovered that "mental anguish put a keener edge on his painting power” and continued to sketch and paint his children for the rest of his career. The later images capture the same austere emotional depth: a dignity or self-possession born of suffering.

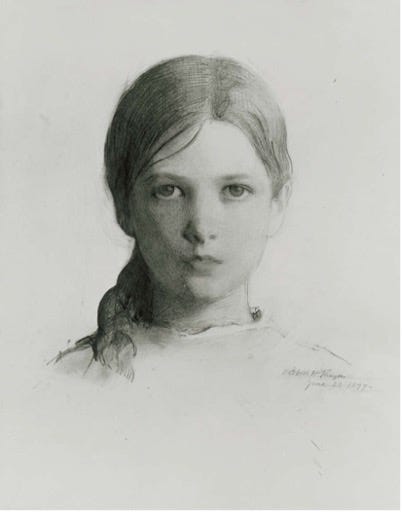

Abbott Handerson Thayer, “Portrait Head of a Young Girl, Gladys Thayer at 11” (1897)

Abbott Handerson Thayer, “An Angel” (1887)

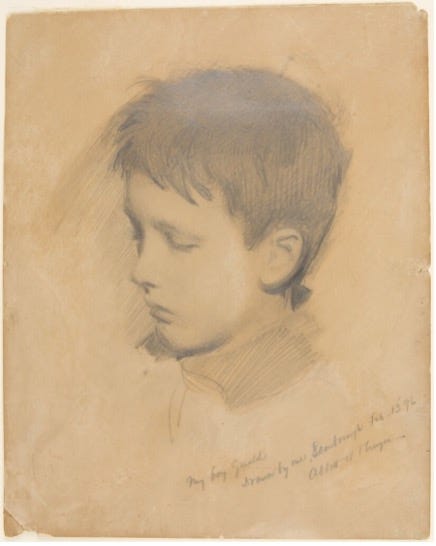

Abbott Handerson Thayer, “Study of the Artist's Son, Gerald” (1897)

This is all (of course) heavily stylized. The Thayer children experienced their share of sorrow, but they also enjoyed a free and artistic (if somewhat unconventional) upbringing in rural New Hampshire, and one should not mistake representation for everyday reality.

Abbott Handerson Thayer with Emma Beach Thayer (his second wife), Gladys Thayer, Mary Thayer, and Gerald Thayer (c. 1905)

Nevertheless, Thayer’s art does capture something poignant about the relation between suffering and selfhood. As the philosopher Peter Roberts notes, doubt and despair are constitutive of human existence. Quoting the Spanish philosopher, Miguel de Unamuno, he writes:

“Suffering is the way of consciousness, and it is through suffering that living beings achieve self-consciousness. To possess consciousness of oneself, to have personality, is to know and feel oneself distinct from other beings. And this feeling of distinctiveness is reached only through a collision, through more or less severe suffering….How would one know one existed unless one suffered in some measure? How turn inward, achieve reflective consciousness, unless it be through suffering?”

If suffering creates the self or reveals the soul, adolescents are interesting not because they are innocent and carefree but because they remain pure and unestranged in their response to hardship, and in that respect they are more authentically conscious than adults. Put differently, while children can be bewildered by suffering just like anyone else, they can also respond with an inspiring solidity and self-assurance.

Insofar as a portrait reveals the inner life of the sitter, it can be a good place to look for these qualities. Examples that I have seen recently include Prudence Heward’s “Girl on a Hill” (1928) and Thomas Faed’s “Visit of the Patron and Patronness to the Village School” (1851). (There must be a million others: feel free to post examples in the comments!)

Prudence Heward, “Girl on a Hill” (1928)

Thomas Faed, “Visit of the Patron and Patroness to the Village School” (1851)

Themes of selfhood-through-suffering are at the center of most coming-of-age novels as well. One thinks of Holden Caulfield’s struggles in The Catcher in the Rye and (more to the point) the way in which he venerates but underestimates his sister, Phoebe. The best comparison I can think of is from another of J. D. Salinger’s stories, “For Esmé, with Love and Squalor,” in which an American soldier finds himself in rural England just before D-Day. Restless and sick of the Army, the narrator steps into a church to hear a children’s choir. He immediately notices a thirteen-year-old girl, her voice “unsentimental” but transcendent. He crosses street for a cup of tea, and a few minutes later the girl enters with her governess and little brother. She sees the soldier and comes over to his table. Her name is Esmé. Her conversation is also frank and unsentimental, that of a “truth-lover” and “a small-talk detester.” Both her parents have died. She is living with an aunt who misunderstands her. She is bored. She hopes to move to America to become a jazz singer. An “avid reader,” she asks if the narrator can write her a story. “It doesn’t have to be terribly prolific!” she assures him. “Just so that it isn’t childish and silly….I prefer stories about squalor.” What is interesting here is that Esmé is precocious but not in any negative sense of the word (i.e., she is not “knowing” or sexualized ). Quite the contrary: while she is whip-smart and sure of herself, she also makes all sorts of mistakes and remains capable of shame. At one point she says, “You seem quite intelligent for an American,” to which the narrator replies that it “was a pretty snobbish thing to say, if you thought about it at all, and that I hoped it was unworthy of her,” and she blushes. That the remark is unworthy of her (and she knows it) merely underscores that she is a person of worth. Salinger identifies the source of that worth in the second half of the story. After the war, suffering from the shakes and on the verge of a nervous breakdown, the narrator trades barbs and dark humor with his bunkmates. But he is brought up short when one of them asks, “Can’t you ever be sincere?” It is then that he returns to his letters and finds one, unopened, from Esmé, the embodiment of sincerity.

All this to say that one aspect of holiness in education is the process of self-revelation and self-recognition that follows a child’s first encounters with suffering, and the sincerity of one’s response—what Søren Kierkegaard would call “purity of heart”—offers each of us a lifelong standard of judgment. It falls to educators to recognize this sincerity in children and to help them recognize it as something sacred in themselves. Art can help.